Your cart is currently empty!

Damaged Goods: My Long Journey in Infertility

TW: depression, mental health, nightmares about miscarriage and stillbirth

At the top of the page, I could read: “diagnosis: infertility”. It’s a strange diagnosis, because infertility, at least in most cases, is not a diagnosis that is any more valid than “insomnia” or “abdominal pain”. Why does a person have difficulty sleeping or have a stomach ache? The root of the problem, rather than its signs or symptoms, should be the diagnosis. After all, it’s only when you have an accurate diagnosis that you can properly arm yourself to tackle the problem, right?

So let’s try again: I’m infertile because…?

The day the sky began to fall

In fact, as my fertility doctor handed me this sheet of paper, she could not give me an answer.

“More specifically, in cases like yours, the diagnosis we make is ‘unexplained infertility’. About 30% of infertile couples receive this diagnosis.”

She was saying “unexplained infertility”, but what I heard was “We don’t know what the problem is. We don’t know how to fix you.” Didn’t I feel so fucking lucky?

I thought back to the first test they ran on me; an ultrasound to check the condition of my uterus and ovaries. It was then, lying on the examination table, that I finally saw it. Proof that something was wrong with my body.

On the screen, I could make out over twenty small follicles in each of my ovaries —little dark holes where there should have been far fewer—confirming to me that there was something wrong with my ovaries, with my hormones, or with my ovulation. Maybe I wasn’t even ovulating.

The term “polycystic ovaries” was nonchalantly thrown about by the doctor as he held the equipment in one hand and manipulated the screen with the other. Finally a clue as to why I still wasn’t pregnant after more than a year after my partner and I started “trying”.

o one understood why I had polycystic ovaries. But at that moment, I wasn’t listening anymore. It was finally official. If I couldn’t have children, it was because of me. I no longer knew what to think. It was destabilizing. I felt numb. I felt, strangely, almost serene. This was the calm before the storm.

And the dark fog settled

Back home with a prescription for Letrozole in hand and the unexplained infertility diagnosis weighing on my heart, a storm was quietly brewing in my mind. It wasn’t just that something was wrong with my body. It was that my body was defective. That I was defective.

My mind was racing. “Is it my fault? Did I do something to cause this? Is it my diet? Is it because I’m too sedentary? Because I drink too often? Because I occasionally smoke weed? Because I had an eating disorder as a teen?”

I was desperately searching for an answer, trying to hold on to something that would make sense of it all and allow me to regain the slightest ounce of control.

If I knew what caused my infertility, I could take steps to change it. Without answers, I was left with resignation, helplessness, self-deprecation, and self-loathing. I was left with irrational “explanations” as to why I couldn’t get pregnant. I became my own abuser.

“It’s because the universe doesn’t want you to be normal.”

“The universe is punishing you for a wrong you have committed.”

“You are not a good partner.”

“You are deficient, damaged, broken, and worthless.”

“You are not a real woman.”

All of the above.

A recurring dream (nightmare?) had come back to haunt me, a dream that had been visiting me in my sleep since I was twelve. In one version, I have my baby in my arms. So beautiful, so vulnerable. Yet, no matter what I do, disaster always manages to catch up to us. I lose my baby, never to find it again, or it succumbs to illness, injury, or a violent accident— drowned, suffocated, or tumbling down a flight of stairs.

As I got older, the dream began to include pregnancy. The baby would be inside of me, alive, moving, and growing, only for me to lose it by having a miscarriage, a stillbirth, or having it torn from my arms after delivery and never seeing it again. I would then be a childless mother. I would go back to being “just” a woman.

Being diagnosed with infertility led me to see these dreams as a sure sign that parenthood was not—never was—for me.

It was as though my body had been trying to tell me, for decades, that it would not be able to fulfill this task, a task that comes so easily and naturally to many.

I was tired of being trapped in a whirlwind of emotions and of constantly wavering between hope and despair, determination and giving up. Again and again, to be tormented by fear and frustration, by painful optimism. When my period was late, I did not allow myself to taste joy and hope, the forbidden fruits that are so accessible to others who dream of having children. An infertility diagnosis is already heavy on its own, but the researcher in me found it even more difficult to see it labeled “unexplained”.

So, I decided that if my doctors couldn’t get me out of the fog, I was going to do it myself.

Knowledge is power

I started combing through books, scientific papers, Wikipedia entries, internet forums, virtual support groups, you name it. I looked at anything that could help me elucidate my unexplained diagnosis or provide me with possible solutions. I was plummeting down the rabbit hole.

Polycystic ovary syndrome? Doesn’t seem to fit. Fragile X syndrome? Nope. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia? Not this one either. Endometriosis? Hold on. Wait just a minute…

Maybe. Most probably.

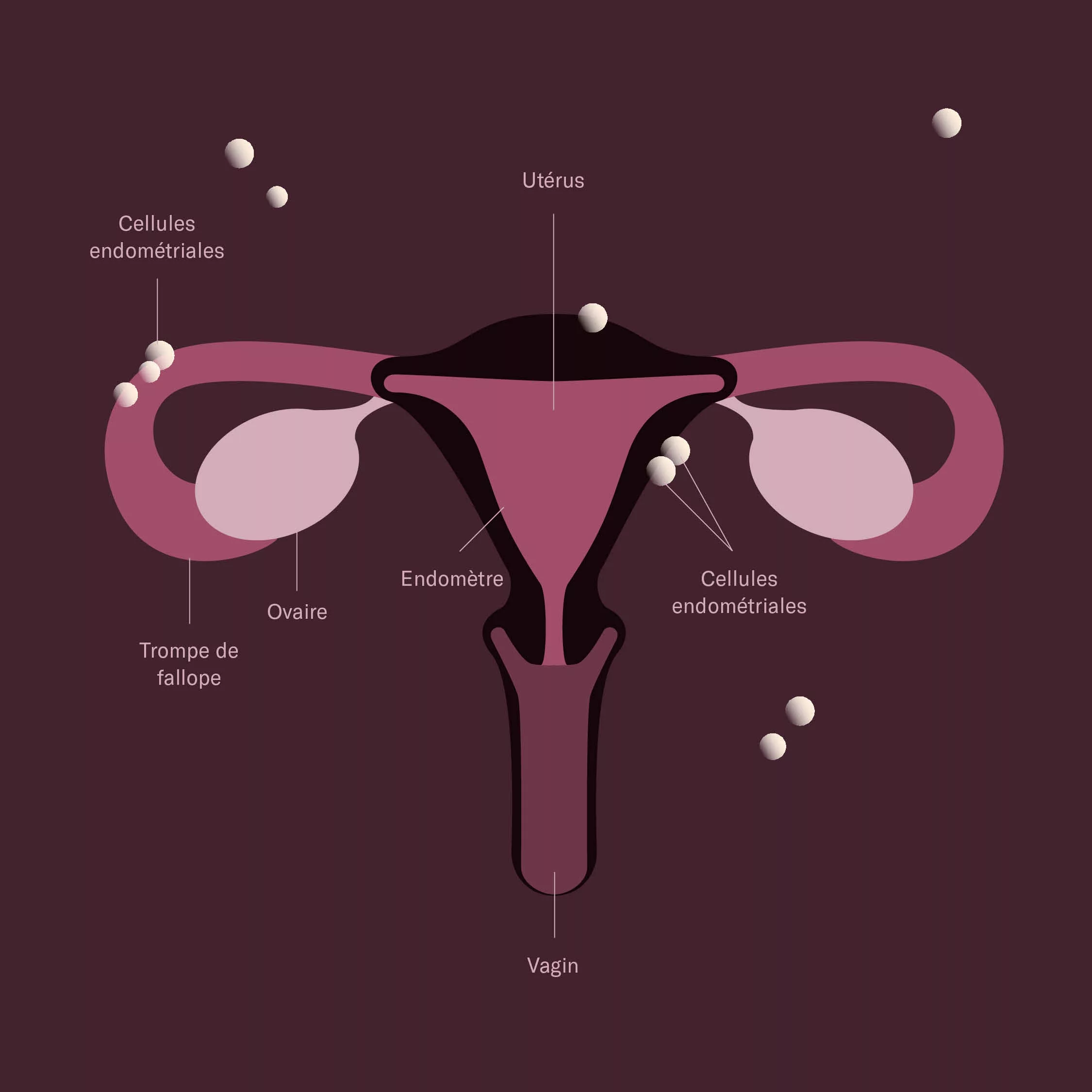

Endometriosis is a chronic condition that occurs when cells similar to those lining the innermost layer of the uterus (the endometrium) grow, implant, and spread outside of the uterus. Endometriosis implants can be found, among other places, on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, intestines, rectum, bladder, and even on the lungs and diaphragm. Like the endometrium, these implants respond to estrogen fluctuations throughout the menstrual cycle. This means that they thicken and bleed every month but, unlike the endometrium, don’t evacuate from the body. In turn, this process can cause inflammation and scarring of the affected organs, which can be very painful.

In Canada, about 7% of people with a uterus have been diagnosed with endometriosis, and almost one fourth of them have been diagnosed with infertility (Singh et al., 2020). The causes of endometriosis are still unknown, and there is no cure. Today, the best treatment is to surgically remove the implanted tissue But the only sure way to make a diagnosis is to confirm the presence of the disease via surgery.

As I have a long history of trauma from medical personnel (that’s another story!), the idea of advocating for myself and convincing my fertility doctor to perform an exploratory surgery to confirm the presence of endometriosis in my body was absolutely terrifying. With my partner’s support and encouragement, my accumulated knowledge on endometriosis, and an episode where I broke down under the weight of helplessness and cried out all the tears in my body in front of the nurse, I eventually managed to convince my doctor to put me on a waiting list for surgery.

Six months later, while I was under general anesthesia, an endometrioma from my left ovary, along with a few endometriosis implants here and there. are) covered in scars and endometriosis. I had finally received my diagnosis: endometriosis, stage 3. So, there you have it.

I wasn’t crazy. I wasn’t imagining things. I wasn’t “just” a drama queen. I am infertile because I have endometriosis. Although I am far from being pregnant, my periods are now much less painful than before, thanks to the surgery. I also find some comfort in this answer—this clue—in the middle of a sea of questions. One step at a time.

As I write this sentence, three years have passed since my partner and I started trying for children. Three years of ups and downs, emotional roller coasters, and growth, on both a personal and relational level.

I know that my value as a person and as a woman does not depend on being able to get pregnant or produce children. I know I have so much more to offer. I am generous, empathetic, and motivated. I have a strong and inquisitive mind. I have a knack for critically dissecting sociocultural phenomena and writing eloquently about them. I am a passionate researcher and educator, an amazing cook, a loving and caring partner, and a loyal friend.

If my partner and I have been able to come through this ordeal with strength and resilience, I have no doubt that we will come to the end of the tumultuous journey of infertility and assisted reproduction, fulfilled.

With or without biological children.

-

Almendrala, A. (2019, 14 of February). There are 4 stages of endometriosis. Here’s what each one means. Health. https://www.health.com/condition/endometriosis/endometriosis-stages

Bushnik, T., Cook, J. L., Yuzpe, A. A., Tough, S. et Collins, J. (2012). Estimating the prevalence of infertility in Canada. Human Reproduction, 27(3), 738-746. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/der465

Cook, S. A. et Cook, D. (2017). The endometriosis health and diet program: Get your life back. Robert Rose.

Endométriose Québec. (2021). Endométriose Québec: Un portail d’informations. Un mouvement de sensibilisation. Une communauté de soutien. https://endometriose.quebec/

Endometriosis Foundation of America. (2016, June 2). Endometrioma: What you need to know. https://www.endofound.org/endometriomas-what-you-need-to-know

Harris, C. et Cheung, T. (2007). SOPK et votre fertilité. ADA.

Haavisto, M. (2020, 11 novembre). Medical trauma: Gaslighting and continuous traumatic stress eating away at your self-worth. Maija Haavisto. https://maija-haavisto.medium.com/medical-trauma-6fa90c6ecab0

Moran, L. J., Misso, M. L., Wild, R. A. et Norman, R. J. (2010). Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human Reproduction Update, 16(4), 347-363. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmq001

Morris, R. S. (2021). Letrozole (Femara) for infertility treatment. IVF1. https://www.ivf1.com/letrozole-femara-infertility/

Organisation mondiale de la santé. (2020, 15 septembre). Infécondité. https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility

Sadeghi, M. R. (2015). Unexplained infertility, the controversial matter in management of infertile couples. Journal of Reproduction & Infertility, 16(1), 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4322174/

Scheffer, G. J., Broekmans, F. J. M., Looman, C. W. N., Blankenstein, M., Fauser, B. C. J. M., De Jong, F. H. et Te Velde, E. R. (2003). The number of antral follicles in normal women with proven fertility is the best reflection of reproductive age. Human Reproduction, 18(4), 700-706. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deg135

Singh, S., Soliman, A. M., Rahal, Y., Robert, C., Defoy, I., Nisbet, P. et Leyland, N. (2020). Prevalence, symptomatic burden, and diagnosis of endometriosis in Canada: Cross-sectional survey of 30 000 women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 42(7), 829-838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2019.10.038

The Endometriosis Network Canada. (2021). The endometriosis network Canada. https://endometriosisnetwork.com/

Yin, W., Falconer, H., Yin, L., Xu, L. et Ye, W. (2019). Association between polycystic ovary syndrome and cancer risk. JAMA Oncology, 5(1), 106-107. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5188