Your cart is currently empty!

Chemsex 101: Increased Pleasure, Risky Practice?

Summary

What is chemsex and what does it involve? What distinguishes party-and-play from other forms of sexualized consumption? Does it have any negative impacts? We demystify it all in this article!

This article is brought to you by CATIE, Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information

Chemsex, also known as party-and-play or PnP, is a sexual practice engaged in primarily by men who have sex with men but also by trans and nonbinary people (Gaudette et al., 2022; Stuart, 2019). It is being increasingly discussed not only in traditional media, but also within our communities.

What does chemsex involve, exactly? What distinguishes PnP from other forms of sexualized consumption? Can it negatively impact sexual health, among other things?

Not only for pleasure

Chemsex involves the consumption of specific psychoactive substances in a sexual context, namely crystal methamphetamine, GHB, or ketamine (Giorgetti et al., 2017; Stuart, 2019).

It is important to note that the substances that are commonly associated with chemsex are not necessarily the same from one place or culture to another. For example, in some European countries, mephedrone, a new synthetic drug, is central to chemsex.

While in Quebec, crystal meth is the substance most closely associated with this practice.

Why do some people choose to indulge in chemsex? For pleasure, unsurprisingly. Consuming the substances mentioned above intensifies bodily sensations and prolongs sexual encounters, increases the likelihood of having more partners, and facilitates the exploration of one’s sexual subjectivity, especially via experimenting with new practices (Lafortune et al., 2021; Race, 2018).

However, chemsex is not just about sexual pleasure. People who engage in this practice also say that they enjoy the fact that it fosters emotional proximity by facilitating discussions, openness, and feelings of deep connection with their partners (Lafortune et al., 2021).

Chemsex: a subcultural practice?

Obviously, many heterosexual people also consume psychoactive substances in a sexual context, but cultural distinctions differentiate chemsex from other forms of sexualized consumption (Florêncio, 2021; Møller, 2020).

Some spaces that are traditionally associated with gay and bisexual men come to mind, such as saunas, where chemsex is more prevalent. Many people who indulge or have indulged in PnP say that their initiation to crystal meth took place in gay saunas or that they frequented this kind of space regularly to indulge in chemsex.

Online spaces have also helped to make chemsex more popular among queer men. Since the early 2000s, websites and dating apps—BBRT and, more recently, Grindr come to mind—have made it easier to organize chemsex sessions and find potential sex partners (Race, 2018). On Grindr, it is quite common to be offered “Tina” or to receive “PnP?” in your direct messages.

As for the substances consumed for chemsex and those consumed by heterosexual people in sexual contexts, the distinctions are striking, particularly when it comes to crystal meth.

In Quebec, crystal meth is used by less than 1% of the population (Institut de la statistique du Québec, 2016). In comparison, according to different studies, between 5.8% and 8% of queer men have used crystal meth in the last six months (Brogan et al., 2019; Community-Based Research Centre, 2021). While no such data is currently available for trans and nonbinary people, qualitative research clearly shows that they are also affected by chemsex (Gaudette et al., 2022; Pires et al., 2022).

In short, the idea is not to deny that anyone can be affected by crystal meth and other substances associated with chemsex; however, if we wish to offer culturally adapted support (and we do!), it is important to recognize that this practice particularly affects sexually and gender diverse communities.

Consequences that should not be overlooked

As mentioned earlier, pleasure-seeking is central to the practice of chemsex; however, the potential social, sexual, physical, and psychological impacts should not be overlooked, especially in cases where the practice is engaged in over a long period of time and with increasing frequency.

On a psychological level, symptoms are mainly anxiety- or depression-related but can also be psychotic, such as paranoia (Bourne et al., 2015; Moreno-Gámez et al., 2022). When chemsex takes up too much space in a person’s life, it can also lead to isolation and loneliness, given that it becomes difficult to maintain relationships with friends, family, and partners (Bourne et al., 2015; Community-Based Research Centre, 2021).

In addition, having multiple sexual partners and hours long—or even days long—PnP sessions can also affect sexual health. Aside from the risk of contracting sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs; Anato et al., 2022), some people report feeling dissatisfied with their sex lives after a period of consumption (Smith & Tasker, 2018). Sometimes, working on oneself is necessary to reclaim one’s sexuality and redefine one’s needs and boundaries.

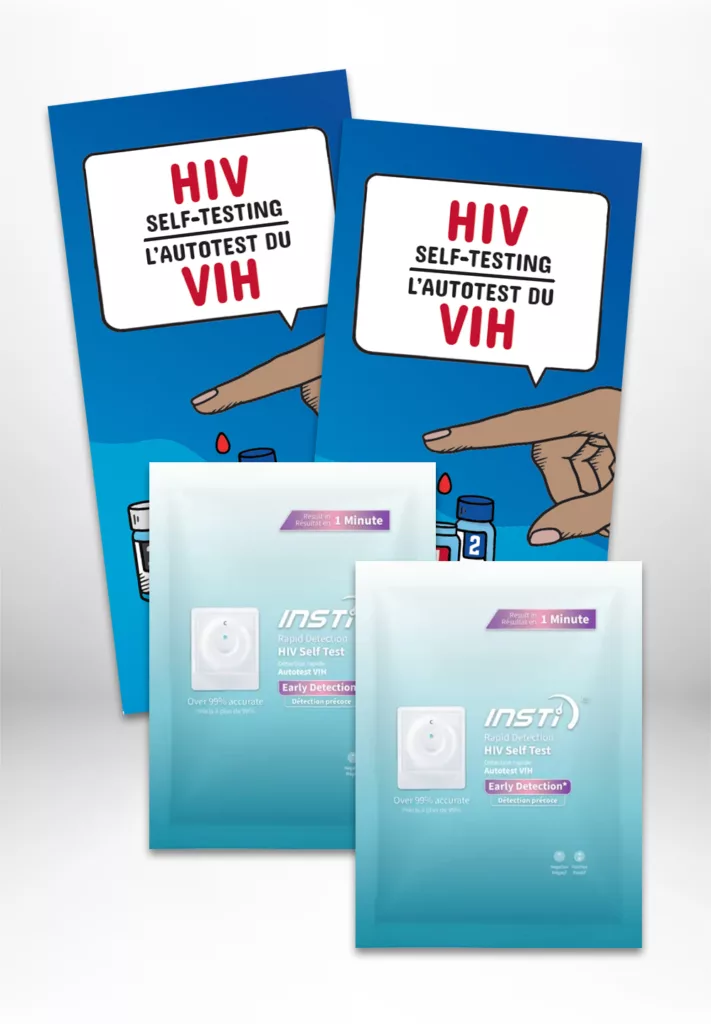

When it comes to chemsex, we can’t avoid the topic of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), and HIV-positive people are overrepresented among people practicing chemsex (Strong et al., 2022; Community-Based Research Centre, 2021). It’s no secret that wearing a condom quite often becomes “optional” during chemsex (Maxwell et al., 2019). Therefore, if a person does not have access to PrEP (a medication to prevent the contraction of HIV) or to HIV testing and treatment, this can increase the risk of infection (Grov et al., 2020).

The sooner a person knows their HIV status, the better! Only a screening test can determine whether a person has HIV.

It’s now possible to perform HIV self-screening tests at home and get the results within one minute. The HIV self-testing kit is free and easy to use.

A few tips for safer chemsex

When addressing chemsex, we should always consider its potential consequences while keeping in mind that not everyone wants or is able to quit.

People who participated in the Canada Research Chair TRADIS’s (trajectories, diversity, substances) PnP within Diversity Project said that they put in place strategies to minimize the risks associated with their sexualized consumption. We have grounded the following recommendations in these strategies.

1. Optimize your sexual health through regular medical follow-ups

Having regular follow-ups with healthcare professionals who are familiar with chemsex and its associated issues can definitely make a big difference. These healthcare providers offer information and resources to promote safer sex and lower risk drug use. For example, access to STBBI screening at a frequency that is adapted to one’s needs as well as taking PrEP can minimize chemsex’s repercussions on one’s sexual health and one’s partners’.

Unfortunately, access to these services can be difficult for people who can’t afford an additional monthly expense or for people who are not covered by RAMQ. Let’s just say that we are impatiently waiting for fast and easy access to free PrEP!

2. Make sure you are comfortable and supported in order to feel safer

Chemsex doesn’t just happen in saunas; it also happens in more private spaces.

Many people say that they prefer to consume only at home or in their regular partners’ homes.

Sticking to familiar locations allows for greater control of your environment, which translates into feeling safe. Also, consuming mainly with regular partners promotes the development of trusting relationships where it becomes easier to set common boundaries and to have respectful sexual encounters.

3. Think about your boundaries, set them… and maintain them!

Setting boundaries regarding chemsex is possible. For example, many people will set aside specific times for this practice to minimize potential social and professional repercussions. Others will self-regulate their drug use by carefully monitoring the quantities they consume. It’s also possible to set clear boundaries relating to the consumption methods used. For instance, certain people will stick to smoking crystal meth and refuse to consume it by injection, given the risks associated with the latter.

That said, crystal meth is often described as a psychoactive substance that leads people to push their boundaries indefinitely until they disappear altogether. To help you define and set your boundaries, you can ask for support from specialized professionals or even from peer workers.

Whether you wish to completely quit drugs and chemsex, think about your practices and potentially reduce your consumption, or learn about safer drug use strategies, a list of resources is available at the end of this article.

Check out our article presenting the testimonials of Éric and Félix, two former chemsex enthusiasts who shared their experience with us.

-

Resources addressing sexual health and harm reduction:

- Your Party and Play Field Guide

- Safer Sex Guide

- Free HIV Self-Test Kit

- Safer Snorting

- Safer Crystal Meth Smoking

- Mapping the Body: Choosing a Vein for Safer Injection

Helplines

- Drugs Help and Referral, Montreal region: (514) 527-2626 | Everywhere in Quebec: 1-800-265-2626

Urgence-dépendance en toxicomanie: (514) 288-1515

LGBTQ+ support and reference organizations

Support groups (Montreal region)

Online help and reference services

- Mybuzz.ca

Chemstory podcast (in which Éric and Félix participated)

Ça prend un village (It Takes a Village) - List of certified addiction resources

Harm reduction

(Supervised consumption site [SCS]/Overdose prevention center [CPS]/Distribution and collection of consumption paraphernalia/Psychoactive substance analysis)

- Montreal: Cactus (checkpoint), Dopamine, Spectre de rue, L’Anonyme (mobile unit), REZO, KONTAK, GRIP (substance analysis)

Quebec City: L’Interzone, SABSA (mobile unit)

Val-d’Or: Clinique Pikatemps

Laval: Oasis unité mobile d’intervention

Chicoutimi: Travail de rue Chicoutimi

Gatineau: BRAS Outaouais (mobile), CIPTO

-

Anato, J. L. F., Panagiotoglou, D., Greenwald, Z. R., Blanchette, M., Trottier, C., Vaziri, M., … et Maheu-Giroux, M. (2022). Chemsex and incidence of sexually transmitted infections among Canadian pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users in the l’Actuel PrEP Cohort (2013–2020). Sexually Transmitted Infections, 98(8), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2021-055215

Bourne, A., Reid, D., Hickson, F., Torres-Rueda, S., Steinberg, P. et Weatherburn, P. (2015). “Chemsex” and harm reduction need among gay men in South London. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26(12), 1171–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.013

Brogan, N., Paquette, D., Lachowsky, N., Blais, M., Brennan, D., Hart, T. et Adam, B. (2019). Canadian results from the European Men-who-have-sex-with-men Internet survey (EMIS-2017). Canada

Communicable Disease Report, 45(11), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v45i11a01

Community-Based Research Centre. (2021). Supporting gay, bisexual, trans, two-spirit and queer (GBT2Q) people who use crystal methamphetamine in metro Vancouver and surrounding areas. https://www.cbrc.net/supporting_gbt2q_people_who_use_crystal_methFlorêncio, J. (2023). Chemsex cultures: Subcultural reproduction and queer survival. Sexualities, 26(5–6), 556–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460720986922

Gaudette, Y., Flores-Aranda, J. et Heisbourg, E. (2022). Needs and experiences of people practising chemsex with support services: Toward chemsex-affirmative interventions. Journal of Men’s Health, 1, 11. https://doi.org/10.22514/jomh.2022.003

Giorgetti, R., Tagliabracci, A., Schifano, F., Zaami, S., Marinelli, E. et Busardò, F. P. (2017). When “chems” meet sex: A rising phenomenon called “chemsex”. Current Neuropharmacology, 15(5), 762–770. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X15666161117151148

Grov, C., Westmoreland, D., Morrison, C., Carrico, A. W. et Nash, D. (2020). The crisis we are not talking about: One-in-three annual HIV seroconversions among sexual and gender minorities were persistent methamphetamine users. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 85(3), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002461

Institut de la statistique du Québec. (2016). L’Enquête québécoise sur la santé de la population, 2014-2015 : pour en savoir plus sur la santé des Québécois – Résultats de la deuxième édition. https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/fichier/enquete-quebecoise-sur-la-sante-de-la-population-2014-2015-pour-en-savoir-plus-sur-la-sante-des-quebecois-resultats-de-la-deuxieme-edition.pdf

Lafortune, D., Blais, M., Miller, G., Dion, L., Lalonde, F. et Dargis, L. (2021). Psychological and interpersonal factors associated with sexualized drug use among men who have sex with men: A mixed-methods systematic review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(2), 427–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01741-8

Maxwell, S., Shahmanesh, M. et Gafos, M. (2019). Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Drug Policy, 63, 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014

Moreno-Gámez, L., Hernández-Huerta, D. et Lahera, G. (2022). Chemsex and psychosis: A systematic review. Behavioral Sciences, 12(12), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120516

Møller, K. (2020). Hanging, blowing, slamming and playing: Erotic control and overflow in a digital chemsex scene. Sexualities, 6(28), 909–925. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460720964100

Pires, C. V., Gomes, F. C., Caldas, J. et Cunha, M. (2022). Chemsex in Lisbon? Self-reflexivity to uncover the scene and discuss the creation of community-led harm reduction responses targeting chemsex practitioners. Contemporary Drug Problems, 49(4), 434–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914509221094893

Race, K. (2018). The gay science: Intimate experiments with the problem of HIV (1st edition). Routledge.

Smith, V. et Tasker, F. (2017). Gay men’s chemsex survival stories. Sexual Health, 15(2), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17122

Strong, C., Huang, P., Li, C.-W., Ku, S. W.-W., Wu, H.-J. et Bourne, A. (2022). HIV, chemsex, and the need for harm-reduction interventions to support gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. The Lancet HIV, 9(10), e717–e725. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(22)00124-2

Stuart, D. (2019). Chemsex: Origins of the word, a history of the phenomenon and a respect to the culture. Drugs and Alcohol Today, 19(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-10-2018-0058