Your cart is currently empty!

Sexual Attraction Versus Romantic Feelings: A Reflection on the Concept of Sexual Orientation

Summary

Are sexual and romantic orientation one and the same? Not really. In this article, sex researcher Léa Séguin teases them apart.

If I told you that I am a woman and that all my relationship partners have been men, what would you assume my sexual orientation to be? What if I added that men’s bodies don’t turn me on, that many of my sexual fantasies involve women, and that I’ve had sexual interactions with other women (without the goal of arousing straight men or getting their attention), would you change your mind?

Most of the time, when we talk about sexual orientation, we refer not only to sexual attraction and behaviours but also to feelings of love. In other words, we talk about it not only in terms of who we fuck (or who we’d like to fuck) but also in terms of with whom we fall in love or have relationship.

Yet, while one’s sexual orientation does tend to match one’s romantic orientation, they are very different concepts.

First of all, what is sexual orientation?

I love you fully, but not completely… I loved your breasts, your feminine voice, your feminine figure, your sweet face. I loved the feminine in you. You have changed. I still love you without your breasts, your feminine voice, figure, and face, and the loss of your feminine features…

Sex is nevertheless essential to both of us, but would I be able to overcome the barrier that is your physical ambiguity to continue to love you as I have done for almost four years?…

The binary hurts my values, but guides my desires. And yet, it distances the erotic feelings I have for you. The dilemma of a heterosexual man in a queer relationship.

Generally speaking, sexual orientation refers to the sexual attraction a person feels towards other people based on their sex or gender. However, according to some researchers, sexual orientation involves several dimensions beyond simple sexual attraction. According to Fritz Klein (1993), it also involves sexual behaviours and fantasies, emotional and social preferences, lifestyle, and self-identification (e.g., straight, gay/lesbian, bisexual, pansexual, etc.).

Even the Government of Canada (2020) includes the notions of love and intimacy in its definition of sexual orientation. It’s therefore not a simple concept with an agreed-upon definition. Scientific research confirms the complex, even messy, nature of this concept—especially, but not only, when it comes to bisexuality.According to the Sexuality and Modern Intimate Ties and Networks study (SMIT’N)—a pan-Canadian study conducted in 2013 with 6,449 participants—39% reported feeling sexually attracted to people of the same sex and of a different sex. This percentage drops to 26% when it comes to having engaged in sexual activity with people of the same sex and of a different sex. In contrast, only 11% of the sample identified as bisexual. This is why it’s important to verify the definitions used by scientists when checking out sexual orientation statistics!

Could we simply determine a person’s sexual orientation based on what arouses them physiologically?

Short answer: nope.

In a laboratory experiment, cisgender men and women of different sexual orientations were asked to watch videos depicting sexual encounters between a woman and a man, two men, two women, and…(ahem)…two bonobos, and then report the extent to which these scenes turned them on (Chivers et al., 2007).

While they were watching the videos, devices measured the levels of penile erection and vaginal lubrication. When comparing the physiological and subjective data, the researchers realized that people’s genital arousal didn’t always match their mental arousal.

The discrepancies between physiological and mental arousal are greater in women than in men, especially straight women (Chivers et al., 2010).

While men’s mental arousal is more likely to match their genital arousal, women tend to exhibit a more conflicting arousal pattern.

More specifically, women’s mental arousal matches their sexual orientation, but their genital arousal is more indiscriminate: women tend to lubricate regardless of whether they are viewing sexual interactions between gay, lesbian, straight… or even bonobo partners! If the scene is sexual in nature, their genitals become engorged with blood.

This is also why we can’t assume that a person is consenting to sex or that they are experiencing sexual pleasure simply based on whether they have an erection or are lubricated. A person can get hard or wet without feeling horny and vice versa. Rather, the research findings like that of Dr. Chivers and her team show that genital arousal is more a matter of physiological reflex than an indication of a person’s pleasure, sexual orientation, or subjective arousal.

It’s therefore important not to assume a person’s sexual and relational reality solely based on their genital arousal or on how they identify.

For example, a woman might choose to identify as straight even though she has lots of lesbian fantasies and has slept with other women, simply because she has only ever experienced romantic attraction to men throughout her life. This self-identification is completely valid. In fact, the most important criterion for determining a person’s sexual orientation is the word they use to describe it, regardless of the “official” definitions.

I’ve always been sexually attracted to women. I like looking at them. I find them beautiful and attractive. I love flirting with them and I often masturbate while thinking about them. On the other hand, I have never been emotionally attracted. I’ve never met a girl with whom I’d like to be in a relationship and I’m always looking to seduce men. It makes it difficult for me to define myself, since it’s a purely sexual attraction. Maybe I just never met the right person?

Speaking of romantic orientation…

Romantic orientation, that is, emotional and affective attraction to other people based on their sex or gender, is an important aspect to consider when we talk about “sexual” identity or orientation.

This view is supported by research. In a recent study, 64% of people who identified as bisexual identified as biromantic, while 23% identified as heteroromantic (Clark & Zimmerman, 2022).

Okay, so not 100% of bisexual people are biromantic, but we can definitely say that 100% of straight people are heteroromantic, right? Think again.

In the same study, 4% of straight participants were not heteroromantic (Clark and Zimmerman, 2022). Similarly, 19% of gay and lesbian people were not homoromantic and 29% of pansexual people were not panromantic.

Distinguishing sexual and romantic orientation is all the more relevant when it comes to asexual people, that is, people who don’t experience sexual desire or attraction toward others. In fact, most asexual people experience romantic feelings and want to be in committed relationships.

According to the AVEN Community Census (Sennkestra, 2014), 47% of asexual people identify as heteroromantic, 20% as biromantic or panromantic, and 10% as homoromantic. Only 19% identify as aromantic, that is, as having no romantic feelings toward others.

I love my boyfriend. I really like him a lot. Our story is one of the cutest in the world. The kind of story you could write a book about, for real. But I think I’m a lesbian, and not just a little.

Sexual orientation is neither categorical nor fixed over time

These discrepancies between sexual and romantic orientation point to the fact that both concepts exist on a spectrum or are a question of degrees rather than of distinct categories.

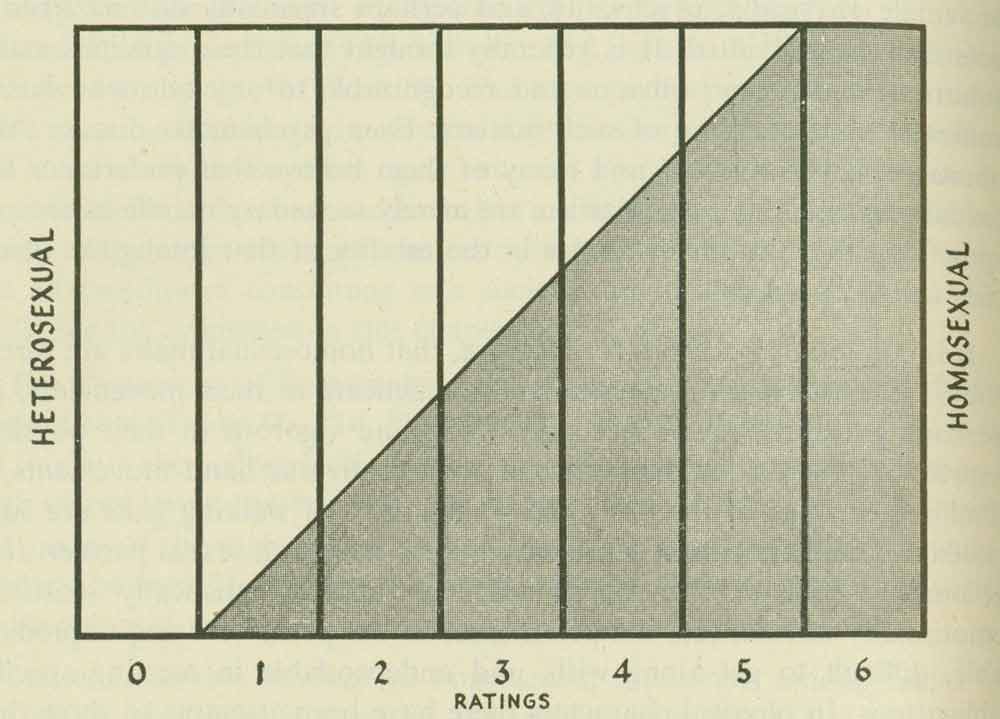

Alfred Kinsey, the grandfather of modern sexology, is one researcher among several who realized that many people don’t fit neatly into either the “heterosexual” or “gay/lesbian” categories, or even into the “bisexual” category. This led him to create the Kinsey Scale ( 1948) to measure sexual orientation on a spectrum.

This scale is far from perfect and is not immune to criticism, but it has nonetheless contributed to the recognition that sexual orientation is more complex than previously thought!

Rating | Description

0 | Exclusively heterosexual

1 | Predominantly heterosexual, only incidentally homosexual

2 | Predominantly heterosexual, but more than incidentally homosexual

3 | Equally heterosexual and homosexual

4 | Predominantly homosexual, but more than incidentally heterosexual

5 | Predominantly homosexual, only incidentally heterosexual

6 | Exclusively homosexual

X | No sociosexual contacts or reactions

Not only is sexual orientation not categorical, it isn’t static: it can change over the lifecourse, and one’s sexuality can adapt or become flexible in response to different contexts and situations.

This phenomenon is called “sexual fluidity.”

Being sexually fluid means to be able to, from time to time, experience a desire or attraction that clashes with one’s “overall” sexual orientation (Diamond, 2008). In other words, the criteria that make one person attracted to another are not fixed and can change over time.

It was long thought that this was a phenomenon that only (or mostly) occurred in women, but more recent research challenges this belief (Katz-Wise & Todd, 2022).

On the other hand, according to a review of studies that have examined sexual fluidity over time, it’s more common among sexually diverse people, especially among bisexual people (Diamond, 2016). Between 26% and 66% of sexually diverse men and between 46% and 68% of sexually diverse women experience sexual fluidity during their lifetime (Diamond, 2016).

***

All this to say that it’s normal if you don’t fit perfectly into one category of sexual orientation. It’s normal to have questions or reflections about your sexual orientation.

It’s normal if your attraction, orientation, behaviours, and sexual fantasies don’t always line up 100% with official definitions.

It’s normal if your sexual and romantic orientations change over the course of your life.

You’re normal, period.

That said, if you’re experiencing anxiety, distress, or doubts about your sexual or romantic orientation, or if you wish to further reflect on this subject, know that you are not alone. The following resources are here to help:

- Project 10 (for LGBTQIA+ youth aged 14 to 25)

- Interligne (for LGBTQIA+ people; in French only)

- Prisme Québec (for cis and trans GBQIA+ men aged 22 and over; in French only)

- GRIS-Québec – L’Accès (for LGBTQIA+ youth aged 18 to 25; in French only)

- RÉZO (for cis and trans GBQIA+ men; in French only)

-

Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C. et Blanchard, R. (2007). Gender and sexual orientation differences in sexual response to sexual activities versus gender of actors in sexual films. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1108–1121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1108

Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., Lalumière, M. L., Laan, E. et Grimbos, T. (2010). Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(1), 5–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9556-9

Clark, A. N. et Zimmerman, C. (2022). Concordance between romantic orientations and sexual attitudes: Comparing allosexual and asexual adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51(4), 2147–2157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02194-3

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Harvard University Press.

Diamond, L. M. (2016). Sexual fluidity in male and females. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-016-0092-z

Fahs, B. (2011). Performing sex: The making and unmaking of women’s erotic lives. State University of New York Press.

Fahs, B. (2009). Compulsory bisexuality?: The challenges of modern sexual fluidity. Journal of Bisexuality, 9(3-4), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299710903316661

Gouvernement du Canada. (2020, 5 octobre). Définitions des orientations sexuelles, identités de genre et expressions de genre (OSIGEG) reconnues à l’échelle internationale. https://www.canada.ca/fr/immigration-refugies-citoyennete/organisation/publications-guides/bulletins-guides-operationnels/demandes-asile/reinstallation/prioritaire-special/orientation-sexuelle-identite-genre/definitions.html

Katz-Wise, S. L. et Todd, K. P. (2022). The current state of sexual fluidity research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 48, 101497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101497

Kinsey, A. C., Martin, C. E. et Pomeroy, W. B. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. W.B. Saunders Co. Ltd.

Klein, F. (1993). The bisexual option. Routledge.

Sennkestra. (2014, 2 novembre). Preliminary findings from the 2014 AVEN Community Census. The ace community survey.https://acecommunitysurvey.org/2014/11/02/preliminary-findings-from-the-2014-aven-community-census/