Your cart is currently empty!

Un Gars Dynamique: Angry Men and Violence on Dating Apps

Trigger warning: this text contains misogynistic and violent comments.

***

“Some girls on the internet are cunts: with all the advances they get in real life, they also have to go say no to guys on the internet.”

“If a man treats you like a queen, cooks, loves children, and helps you clean, the least you could do is to not get a ‘headache’, you bitch!!”

“Don’t doll yourself up too much or I’ll sexually assault you.”

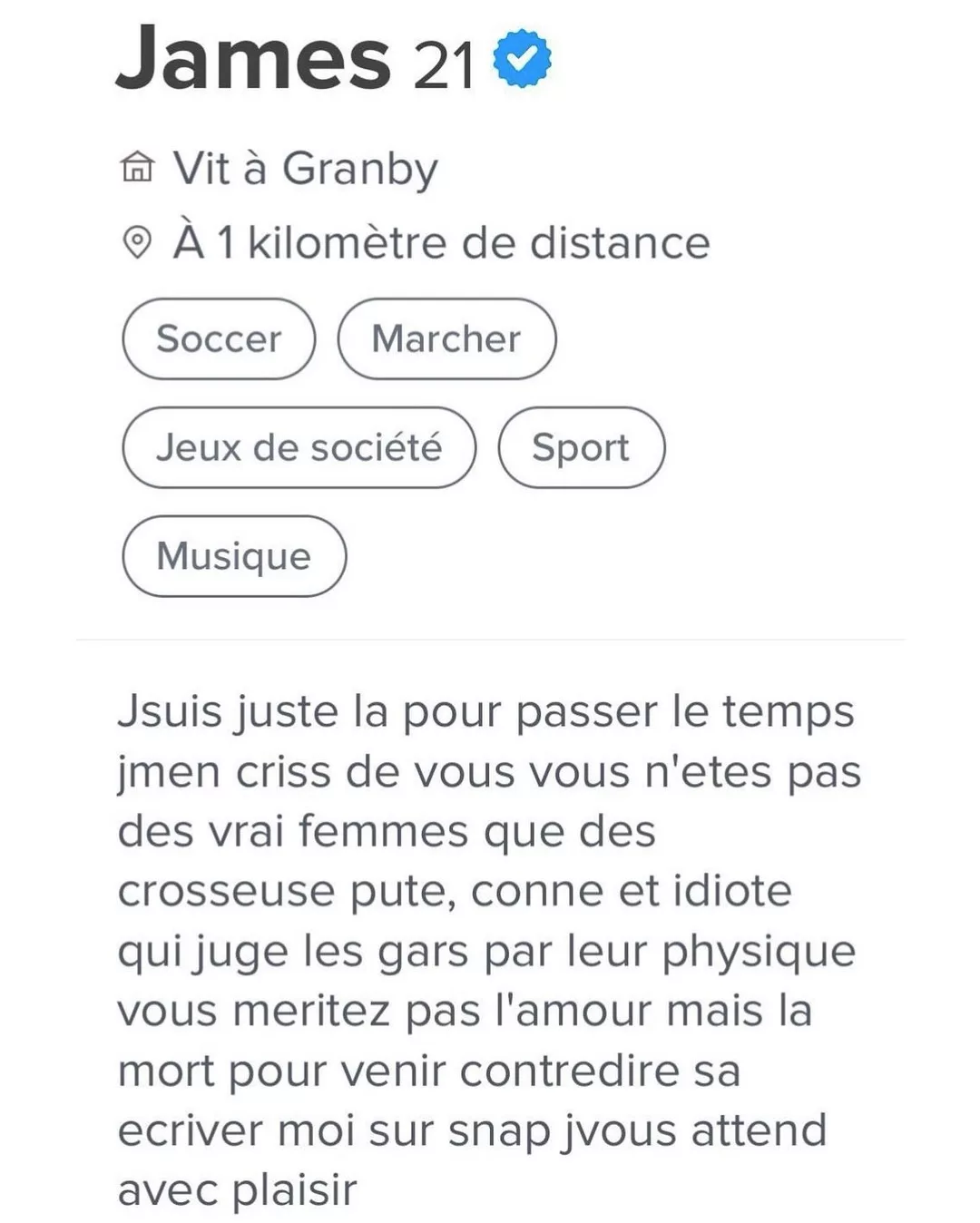

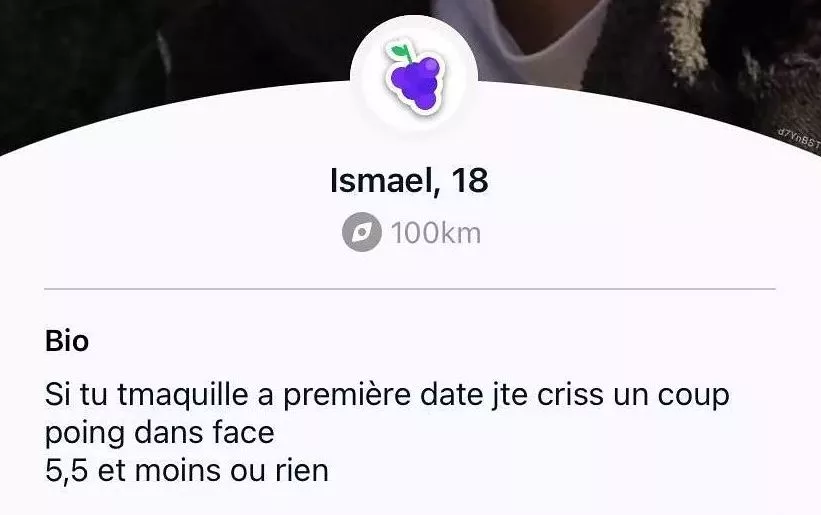

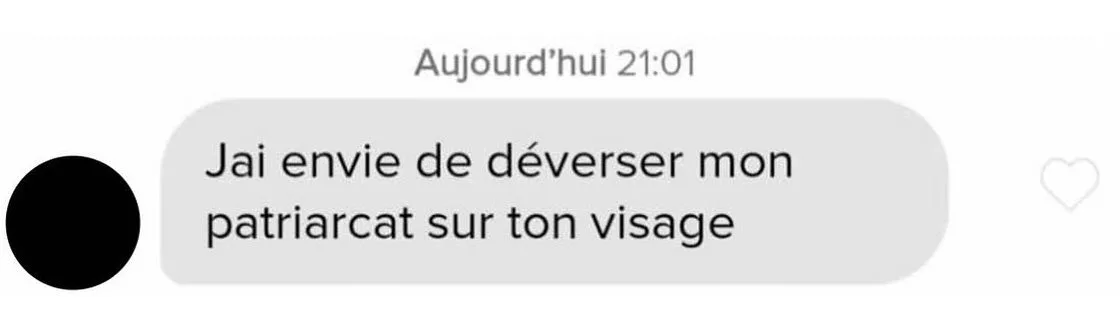

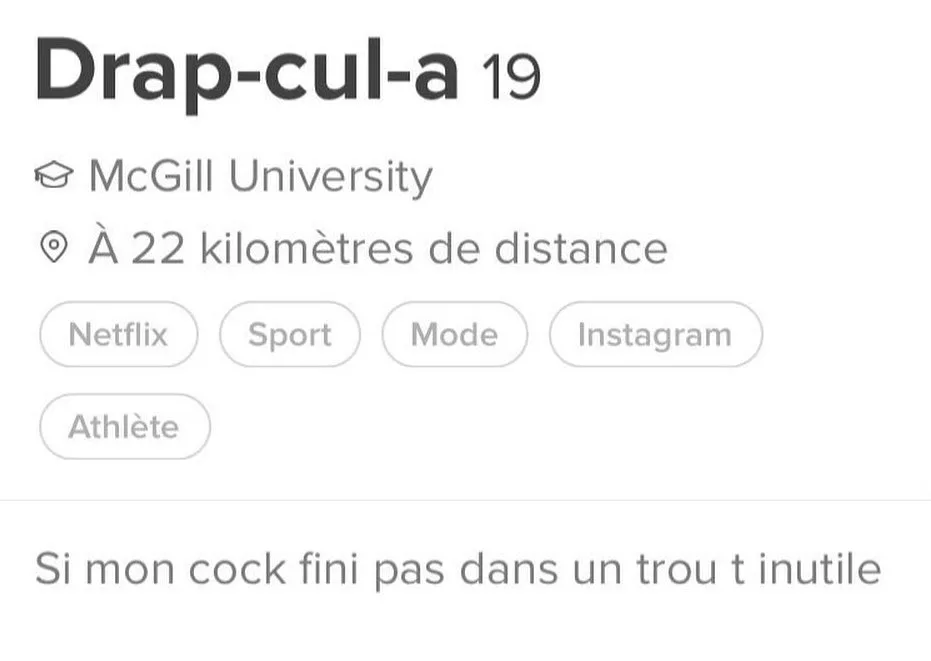

These messages are just a few examples of the misogynistic violence that is viciously and unabashedly displayed on dating apps (and they’re not even the worst), whether on user profiles or in direct messages.

According to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, more than half of women aged 18 to 34 report having received a sexually explicit image or message without their consent on a dating platform (Anderson et al., 2020). Further, one in five women say they have been threatened with physical violence, which is roughly twice as many as men of the same age.

Content creator Margot Chénier has no trouble believing these statistics: she has seen how prevalent violence is on dating apps, firsthand, especially male-perpetrated violence, when she created a Tinder account a few years ago.

She began posting screenshots of particularly degrading profile descriptions on her personal Instagram account. A ton of women reacted to her content by confiding in her about their own experiences and discomfort with this reality.

And so, in the fall of 2020, Un gars dynamique was born: an Instagram account where Margot posts the best of the worst of dating apps.

We spoke with her to learn more about her approach.

Update: After we interviewed Margot, Instagram deleted her account (@un.gars.dynamique) for having “repeatedly posted content that violates the Community Guidelines” (while the shared content’s violence was precisely what Margot was denouncing). After reflection, the activist decided to keep going by opening a new account (@ungarsdynamic). The images displayed in this article come from the archives of her original account.

You say on @ungarsdynamique that it’s a denunciation account. What are you denouncing, exactly?

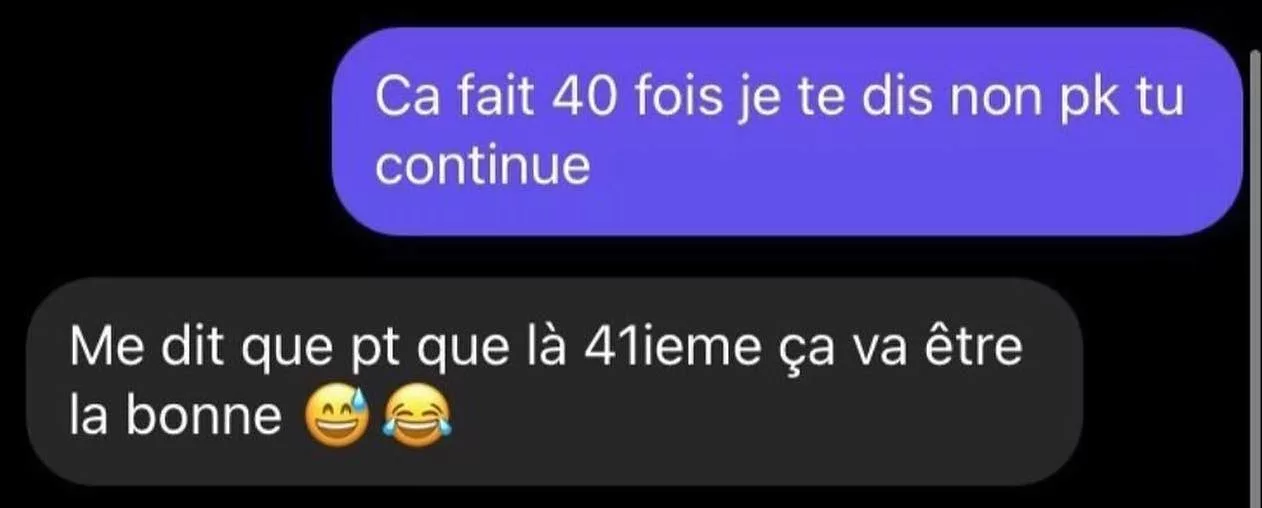

A lot of things [laughs]. First, violent behaviour. This is the thing that I find the most absurd on dating apps: the insulting messages that women receive—in the vast majority of cases, women are the recipients of such messages—when they don’t reply or when they refuse to give out their phone number or their Snapchat… Basically, when men face rejection. It’s super common that it turns into insults, which are obviously uncalled for, totally gratuitous.

So, I’d say that what I’m trying to denounce is machismo and misogyny, but there’s also fatphobia, racism… in short, all the problematic behaviours of angry men.

Exactly, you only post profiles and messages from white cishet men. Why this choice?

I don’t always have access to photos of the person, but I indeed do try to only post white cis straight men’s profiles. Of course, people don’t always write their sexual orientation or gender in their profile, so I can’t guarantee 100%. But I make that choice because I try to focus on people who don’t come from the margins of society or who haven’t experienced much oppression.

How do you select the profiles or direct messages that you post?

It happens organically. When someone sends me screenshots of messages or profiles that contain blatant violence or problematic behaviour, I automatically save it to my phone. I also like to publish profiles that have an original twist or that display bad jokes. I think it adds a little spice to my page!

When I realize that I’ve published several super violent profiles in a row, I try to publish a funnier, lighter one, albeit still problematic.

How would you define toxic masculinity?

On social media, I’d say that toxic masculinity is very ego-related. I feel like men who are on dating apps and who don’t really get matches take it super personally and blame it on women: we’re too picky, we go after “bad boys” and ignore them, the “good guys”… It’s always “because women.”

So, I’d say that toxic masculinity on dating apps is essentially men with fragile egos who can’t handle rejection. Much of the time, it comes out in angry and aggressive outbursts.

By dint of seeing so many manifestations of toxic masculinity, have you thought of possible solutions to stop men adopting such violent behaviours?

Honestly, I really often—several times a week—receive written messages from cishet white men who tell me, “Wow, I wasn’t aware of all this. I had no idea. Thank you.” This is probably why I keep doing this without becoming psychotic or depressed [laughs]. It really gives me hope.

I think it helps to call men out on their behaviour, because not everyone is aware of how often, on a daily basis, a woman fears for her safety—even in the West, even in communities where you should be relatively safe, even when you have privileges such as white privilege.

Many guys who don’t do that kind of stuff, who see themselves and their friends as good people, think this reality doesn’t exist. But, just because you don’t send violent messages doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. Sometimes, your seemingly nice friends are some of the guys who send those uncool messages, and you have no idea. These messages aren’t only, “I’m going to kill you if you don’t give me your number.” Sometimes, they’re comments to a woman about her breasts, written to someone they’ve never even spoken to before.

So, I think that denouncing is one of the best things we can do right now, because it makes people aware of this reality.

Beyond that, I think part of the movement must come from the men themselves. You can’t fix toxic masculinity for them. But I still think that, with the Me Too movement, we’re heading in the right direction.

I sometimes unsubscribe from your account and re-subscribe on and off again because I sometimes feel exhausted from reading such violent comments. I imagine that you also get tired of reading them. What do you do when that happens?

Yes, it happens. I take breaks. Sometimes, that means taking Instagram off my phone for a while.

At the beginning, I remember sometimes crying as I read the messages, because it was just too much. I couldn’t bear it. But at some point, I not only realized the full extent of the violence that exists out there, but also that it could change. I’ve felt less affected since then.

I am also lucky to be surrounded by three or four cis men who are allies, so it gives me a bit hope to be around them. The messages I receive too! Every day there are people who thank me for what I do.

SOn your account, you publish the profiles and messages that your followers share with you, but you specify that your account doesn’t do any kink shaming, nd therefore, that you don’t accept any submissions that shame or make fun of kink. However, if someone imposes his kink in his profile or in a private message, you say that it’s different. What do you mean by that?

I was getting a lot of screenshots of profiles with bios like, “I want someone to tie me up and do this to me.” But stating your kink in a respectful way in your bio is not problematic in itself. What’s problematic is when people write stuff like, “I’m going to tie you up like a little bitch, and won’t let your mouth rest.” Which is a real example, by the way.

Having sexual fantasies is OK, but you can’t impose them on people like that. Before saying that to someone in a private message, it’s important to first have their consent.

You also refuse submissions that make fun of people’s grammar or writing skills. Why?

It’s a question of ableism : when you laugh at someone for their poor writing skills, you don’t know what education he’s received, if he has a learning disability or a disorder that affects concentration, if he’s dyslexic, or if French isn’t his native language… Besides, bad grammar and incorrect homophones are the least aggravating things in the problematic bios I share!

How do you think dating apps could be safer for women? What kind of measures could be put in place to reduce violence?

In an episode of the À quoi tu jouis? podcast, Laïma interview researcher Christopher T. Dietzel to discuss the place of dating apps, consent, unsolicited dick pics and other online violence, especially that experienced by marginalized communities.

It could clearly be improved. Recently, on Tinder, I noticed that if certain words are sent in a conversation, a small bubble appears that asks you if you’d like to report the message if it’s indeed violent.

But, I think much more could be done: after all, on Instagram, I constantly get posts deleted because the application detects violent content. So, why are these profiles still on Tinder? If Instagram’s algorithm can detect violent messages, there’s no reason why dating apps can’t.

What advice would you give someone who is interested in using dating apps but who is afraid of being on the receiving end of violence?

I’d say that some apps are safer than others. Personally, I think OkCupid is pretty good, because it can collect lots of information about your values. So, if you indicate that you’re a feminist, that you’re interested in social justice issues, and that you consider respect for women to be important, the app won’t show you the profiles of people who say they don’t think it’s important.

Otherwise, the only advice I have is to not hesitate to denounce violence when you experience it. You can report the account, you can take a screenshot and send it to me, you can talk about it to those around you. You don’t have to deal with it alone.

If you want to share your dating app experiences, you can also leave a confession in our Confessional.

-

Anderson, M., Vogels, E. et Turner, E. (2020). The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/06/the-virtues-and-downsides-of-online-dating/

Díaz del Castillo, P. (2019). Qu’est-ce que le capacitisme? Quelques réflexions… [What is ableism? A few thoughts…] Association québécoise interuniversitaire des conseillers aux étudiants en situation de handicap. https://www.aqicesh.ca/actualites/quest-ce-que-le-capacitisme-quelques-reflexions/

Linder, C. et Johnson, C.R. (2015). Exploring the Complexities of Men as Allies in Feminist Movements. Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.31274/jctp-180810-37

Scott, H. (2003). Stranger Danger: Explaining Women’s Fear of Crime. Western Criminology Review, 4(3), 203-214.

Vivid, J., Lev, E.M. et Sprott, R.A. (2020). The Structure of Kink Identity: Four Key Themes Within a World of Complexity. Journal of Positive Sexuality, 6(2).

Wirtz, A.L., Perrin, N.A., Desgroppes, A., Phipps, V., Abdi, A.A., Ross, B., Kaburu, F., Kajue, I., Kutto, E., Taniguchi, E. et Glass, N. (2015). Lifetime prevalence, correlates and health consequences of gender-based violence victimisation and perpetration among men and women in Somalia. British Medical Journal, 3(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000773